The

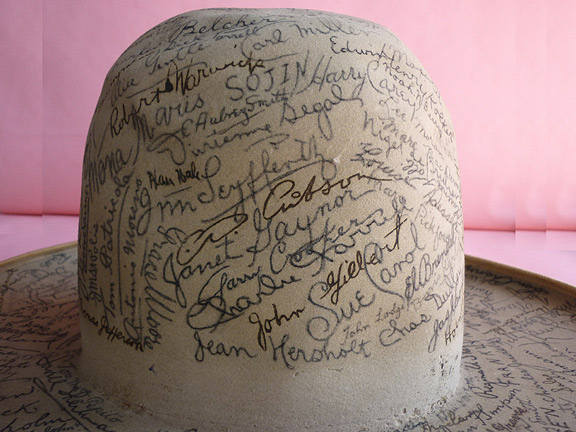

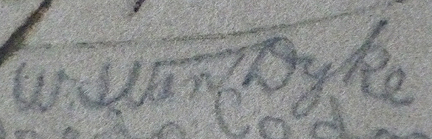

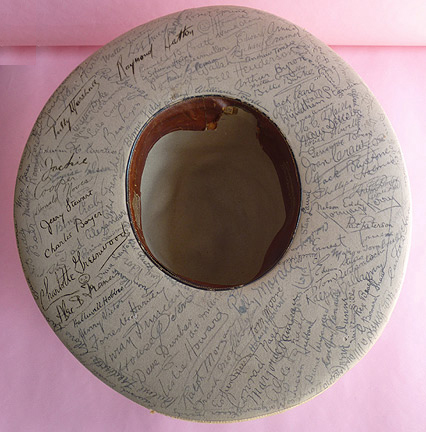

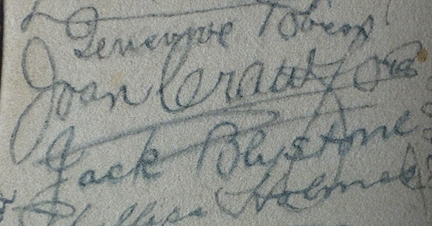

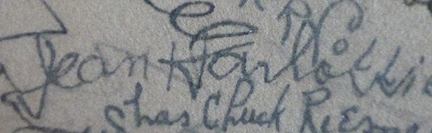

collection is unusual in that all of the signatures are on

one

vintage Stetson cowboy hat - on the crown, on the brim,

and even under

the brim. The signatures, executed by fountain pens

(this was

before the days of ballpoints), virtually all date from

the 1928-1936

time

period. I immediately thought of it as "The

Hollywood Hat."

This was an

interesting era in Hollywood history. In the late

20's, the

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded,

Grauman's

Chinese Theater started collecting foot and handprints,

WAMPAS Baby

Stars were all the rage and movies went from silent to

"talkies." As I researched the names on the hat, I

came to

realize how the switch to talking pictures affected many

of the hat's

signers. Like fictional George Valentin in "The

Artist," lots

of big-time careers crashed with the advent of sound,

including these

hat signers - Eleanor Boardman, Norman Kerry, Pauline

Starke, Antonio

Moreno, Victor

Varconi, Aileen Pringle, and most famously, John Gilbert.

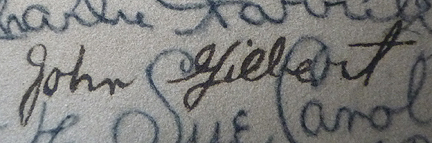

John

Gilbert

John

Gilbert

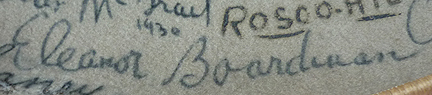

Eleanor

Boardman

Eleanor

Boardman

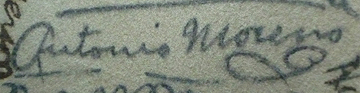

Antonio

Moreno

Antonio

Moreno

WHOSE

HAT

WAS THIS?

But the first question on my mind was "Whose hat was

this?" I

came up with what we can call Theory #1.

Theory #1: The Stetson hat was worn by one very

dedicated

autograph collector who spent years haunting Hollywood

Boulevard. The doorman at the Brown Derby probably

knew him

on sight. And what a great gimmick. Rather

than

shoving pen and paper at a movie star, ask them to sign

a ten gallon

cowboy hat. Who could resist? Judging by the

sheer

number

of signatures, no one.

As I made a list of every name on the hat, it slowly

dawned on me that

quite a few of the signers were contract players at

M-G-M and, to a

lesser extent, at Fox, the two studios on the West Side

of Los

Angeles. There's hardly anyone from Warner

Brothers,

Paramount

or RKO, all located on the other side of town.

I decided to vote Theory #1 off the island, and

developed Theory #2.

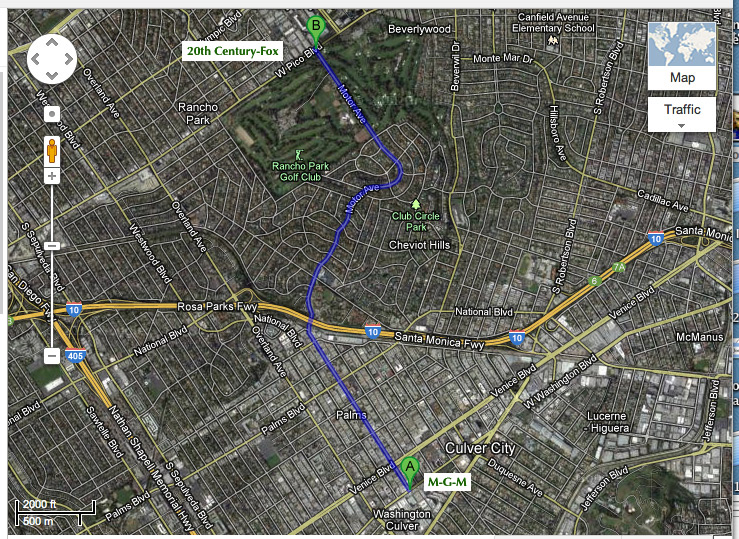

Theory #2: The dedicated autograph collector hung

out at the

front gates of M-G-M and Fox, which are conveniently

connected by a

winding street called Motor Avenue. Local lore is

that Motor

Avenue was built to cut down on the commute time between

the two

studios; it only takes about 10 minutes to toodle up or

down Motor

Avenue.

Motor Avenue

connects M-G-M and 20th-Century Fox

Motor Avenue

connects M-G-M and 20th-Century Fox

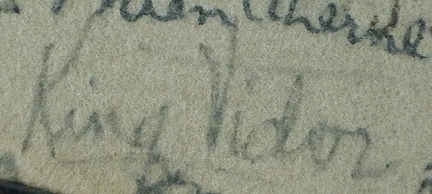

But then I started spotting autographs of directors

(unless they're

Spielberg or Hitchcock, who the hell asks a director for

his

autograph?) - King Vidor, W.S. Van Dyke, Roy Del Ruth,

Robert Z.

Leonard, Thornton Friedland, Alfred E. Green, Archie

Mayo, Eddie

Buzzell. And

I thought,

okay, it's time to tool up Theory #3.

King Vidor

|

W. S. Van Dyke

|

Theory #3: This hat belonged to an insider -

someone who had

frequent access to the two studios. Maybe they

were an extra

or maybe the hat belonged to a movie crew member. The

only thing

working against Theory #3 is an immutable law of

Hollywood once behind

the studio walls - don't bother the stars.

The hat is a crazy quilt of

signatures, and I kept seeing new

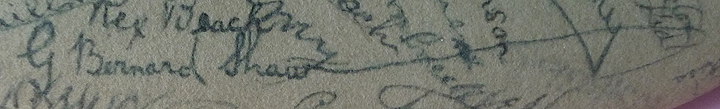

names. On the underbrim, I was stopped cold by the

signature

of British playwright G. Bernard Shaw. What on

earth is the

signature of George Bernard Shaw doing on this

hat? I know

Shaw visited Hollywood in his lifetime.

Once. In

1933. For just three hours.

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

I asked myself

again: Whose hat was this?

Over 90 per cent of the names on the Stetson were actors

and actresses

plus the aforementioned directors as well as a gaggle of

World

Heavyweight Boxing Champions (more about them

later). And

then, in the midst of all this celebrated celebrity,

there were the

"John Hancocks" of four men who worked in studio make-up

departments. No set designers. No costume

designers. No sound recorders or music

arrangers.

Just four make-up men. Curious.

Theory #4: The hat belonged to someone in the

make-up

department at M-G-M or Fox. Make-up people would

have daily

access to stars at their most relaxed and vulnerable,

when they're just

sitting there with nothing better to do than autograph a

cowboy hat.

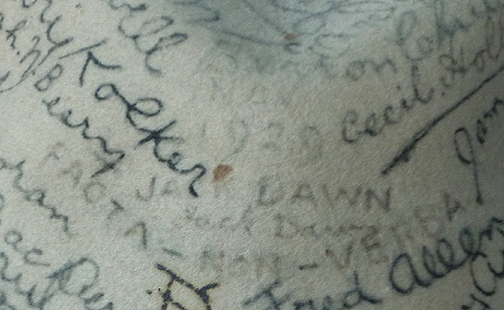

The four make-up artists who signed the hat were:

Jack Dawn,

who led M-G-M's Make-Up Department from 1935 to 1950,

and who is best

known for his ground-breaking work on "The Wizard of

Oz";

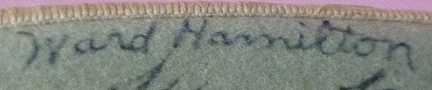

Ward Hamilton with a raft of credits for Errol Flynn

movies at Warner

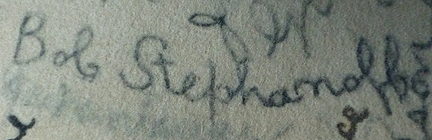

Brothers; Blagoe "Bob" Stephanoff, who worked on such

Samuel Goldwyn

classics as "Wuthering Heights" and "The Best Years of

Our

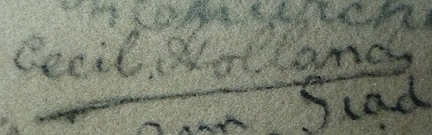

Lives"; and Cecil Holland, a silent screen

character actor

who started the first big studio make-up department in

1925 at

newly-formed M-G-M. Unfortunately, there's no

chance to ask

them if they remember signing the hat; all four men

passed on many

decades ago.

Jack Dawn

|

Ward Hamilton

|

Bob Stephanoff

|

Cecil Holland

|

An

Eyebrow

is Born - Testing eyebrows -- and the "Crawford

Smear" --

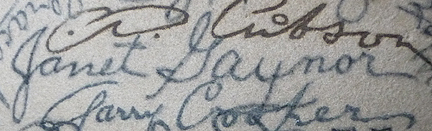

on Janet

Gaynor in 1937's "A Star is Born." One of the

best movie

make-up department scenes -- ever.

Janet Gaynor

Janet Gaynor

So, I've got a hat filled with

autographs from the 1928-1936 time period, which was

originally

situated (maybe) in the M-G-M and Fox make-up

departments.

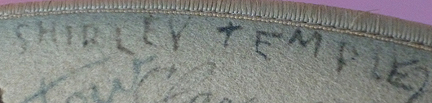

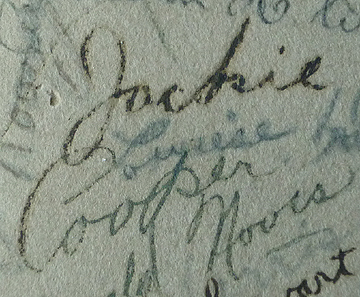

Only three people who signed the hat are still alive -

Shirley Temple,

Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper.

Shirley Temple

Mickey Rooney

Jackie Cooper

ALWAYS

CHECK

THE OBITUARIES

As I'm pondering how to

proceed in unlocking the provenance of the hat, I read

in the LA Times

that Jackie Cooper just died. Oops. Make

that two

people still alive. And honestly, Mickey and

Shirley must

have had seriously wackadoodle childhoods. Rooney,

born in

1920, had been in movies since the age of 6, racking up

over 40 screen

credits by the time he was 10. As for Temple, an

actor once

told me of being on the Fox lot in the 1930s and as he

walked by

Shirley's bungalow, he could see her outside, marching

in a circle

repeating to herself: "I am Jesus. I am

Jesus." I'm not accusing Shirley of a

son-of-god-like ego (by

all accounts, she grew up to be grounded and "normal");

it's likely

that she was just repeating something an adult said in

her presence

(probably with a cigar dangling from the corner of his

mouth): "The kid is as big as Jesus!"

Like I said - wackadoodle childhoods. Temple was

the number

one box office star from 1935-1938; Rooney was number

one from 1939 to

1941. Autographing a cowboy hat wouldn't be in

either

Mickey's or Shirley's top 100 memories during their kid

stardom.

(I wrote to Temple and Rooney, but never got a

reply.)

I did some

research on early studio

make-up departments. And

I found out… almost nothing. Hardly any movies

have make-up

credits during the 20's and 30's and the bios I find of

Dawn, Hamilton,

Stephanoff and Holland are brief. There is a

mention that

Holland had a daughter, Margaret, born in 1927, who

excelled as a portrait artist. I find out,

amazingly, she's

still active with a website. Just before I left

for a

vacation in Italy, I emailed her an inquiry in the

slimmest,

off-chance, Hail-Mary-pass kind of way, asking if she

remembered going

to her Dad's "office" when she was a very little girl

and seeing a

beige cowboy hat covered with movie star signatures

somewhere in the

M-G-M Make-up Department. We all have odd memories

from our

childhoods, and I hoped the hat was one of hers.

Several days

later, I'm in an internet cafe in Rome plowing through

some business

emails when I see Ms. Sargent has replied. I open

up the

email and read:

"Dear

Mr. Blitman,

I

was delighted to receive your email

with a request for information about the

cowboy

hat. You have reached

the right person for

its background. It was my father,

Cecil Holland, who got all those

signatures from the

actors who sat in his makeup chair… many of whom later

became friends

… It was his

pride and joy."

Bingo. Eureka.

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious. Cecil Holland

didn't just

sign the hat. He owned

the hat. Suddenly, just like

that, there's divine provenance.

How do you say "I'm doing the happy dance" in

Italian? I have

no idea, but I do know I spent the day exploring the

Colosseum with my

thoughts binging and boinging like a pinball machine

with alternating

visions of Christians, gladiators, and lions and

Joan Crawford

being

made up for "Our Dancing Daughters."

CECIL WHO?

Los Angeles has always attracted

certain men and women whose dreams and

abilities are on steroids, and to whom no 9-to-5 job can

do

justice. These people are larger-than-life in some

respects,

and need to exist outside the box in order to

flourish. They

carry bazookas of ambition and talent, while the rest of

us are armed

with water pistols. I think of them as

"characters," not in

the Damon Runyon kind of way, but as one-offs, unique in

what they add

to the world. Cecil Holland was this kind of

"character."

Cecil

Holland

in 1925, photographed by Clarence Bull.

Of medium stature with

even features, thin lips and impossibly thick and wavy

hair, Cecil was

an accomplished actor, engraver, etcher, photographer,

painter, jewelry

maker, sculptor, wood carver and most importantly, a

dedicated and

deeply talented make-up artist. He was

simultaneously

admired, respected and liked by co-workers. As a

mentor and

teacher to a generation of other make-up artists,

Holland was more than

well-regarded and remembered with great fondness as the

"Father of

Movie Make-Up."

Cecil Holland was born in very comfortable circumstances

in the

Victorian era on May 29, 1887 in Gravesend-on-Thames,

not that far

outside London, England. The location was key, as

Cecil was

descended from a long line of ship's captains licensed

to pilot on the

Thames River. Although he was fascinated with

painting and

sculpting as a child, Cecil was expected to continue the

family

tradition, and, at 15, dutifully or excitedly, or both,

he apprenticed

on a three-masted barque, "The Harold of London,"

making a

round-the-world voyage.

As 1902 predates the opening of the Panama Canal by a

dozen years, the

westward-bound ship went all the way around South

America, through

legendarily rough waters, and then up the west coast of

North

America. After six months of being seasick every

day (giving

a new meaning to the term: "Heave, Ho"), Cecil had

had

enough, and bid farewell to his "destiny." He

jumped ship in

Vancouver, Canada.

Holland made his way to Seattle, where, in 1904, he

joined the first of

several traveling theatrical road shows. While

wending and

winding through the west over the next decade, he

learned acting,

graduating from "member of the crowd" to speaking

parts.

Because he wasn't the leading man type, he absorbed all

he could about

make-up, having determined that versatility in one's

appearance was the

way to succeed as a character actor.

Cecil finally wound up in Los Angeles in 1913, at the

very dawn of the

motion picture business, when film production companies

were springing

up everywhere. He briefly worked as a stuntman in

Westerns

for three bucks a day and sometimes found himself the

target of live

ammunition (because films were silent, directors needed

the visual

"ping" of flying dirt and nothing could do that as well

as real

bullets). With self-preservation as motivation,

Cecil

successfully promoted himself as a very castable

character actor,

broadcasting his ability to transform himself - through

make-up - into

a vast variety of character types and ethnicities.

He got his

first verifiable screen acting credit in 1914 in "The

Mystery of the

Seven Chests."

He simultaneously publicized himself as a make-up

expert. In

the September, 1916 issue of "Picture-Play," a trade

magazine, Holland

wrote an article called "Making Myself Miserable,"

in which

he describes, in detail, some of his

transformations-thru-make-up

including that of "Death" itself in "Man With an Iron

Heart" (you start

with a pound of putty to turn the face into a skull).

Holland claimed that creating facial features that

express a

character's thoughts "is the greatest joy I have ever

known."

Sounds like someone has found his metier.

Holland's

article

"Making Myself Miserable"

appeared

in

this issue of "Picture-Play Magazine.

That's

Norma

Talmadge on the cover.

|

Cecil

Holland made

up as Death

in

"Man With An Iron Heart."

|

A gifted make-up man

like Holland was a golden asset to any film

production.

Actors were responsible for doing their own make-up and

many of them

were inept or wildly inconsistent from day to day.

It was not

uncommon to have to throw out a day's worth of film

because of how bad

some make-up looked on screen. If you hired

Holland to act,

you also had him to work on the other actors'

make-up. He

thrived on these challenges.

From 1913-1917 Cecil made at least 22 movies, most with

melodramatic

titles like "The White Light of Publicity," "The

Sacred Tiger

of Agra" and "The Lad and the Lion." Some of the

movies were

produced by Fox and Paramount, but mostly they were made

by Selig

Polyscope, where Holland was a contract stock

player. It is

very likely Holland made far more than 22 movies during

this

period. Unlike today, where listing the cast and

craftsmen

who worked on a film can take an endless 7 or 8 minutes

to scroll out,

Hollywood was very stingy with credits in those days,

and usually just

a handful of the actors appearing in a movie got screen

credit. And since a huge majority of the films

made during

the Teens are lost, it is, a century later, an era

cloaked in some

mystery. Cecil's early years in Hollywood wear

that same

cloak.

When the U.S. entered World War 1 in 1917, Cecil

very quickly

enlisted in the Army and was assigned to the 316th

Engineers, Company

C, 91st Division. After training for more than a

year,

Holland arrived in France in August of 1918, just in

time for fierce

and ceaseless fighting in the Argonne region. The

316th

Engineers' job partly involved repairing roads, bridges,

and train

tracks

to speed the advance of the U.S. troops. This was

often front

line work, and highly dangerous. Unlike dodging

bullets as a

stuntman, this was the real thing.

Cecil Holland, dressed for combat, in Europe in 1918

.

THE

MAN

OF 1,000 FACES

Holland returned to Hollywood by early 1920. Given

that a

three-year absence in Hollywood is like a 50 year

absence anywhere

else, it's a testament to Holland's talents that he was

back in

business almost immediately, transforming

well-known wrestler

Bull Montana into a gorilla for a melodrama, "Go and Get

It."

To help publicize that he was back in town, Cecil wrote

a series of

articles on movie make-up for "Camera" magazine, a

motion picture trade

publication, and was the solo performer in a

widely-distributed

"Camera"-produced short called "The Mind of Man."

In it,

Holland plays all five very different-looking

characters, and at the

end of the short, shows the viewer how he did it through

the magic of

make-up.

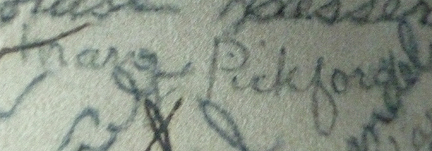

Mary Pickford

In 1921, Cecil did make-up for the Mary Pickford

films

"Little Lord Fauntleroy" and "The Love Light," as

well as a

Jackie Coogan starrer, "My Boy." At the time, Mary

Pickford

was inarguably the most famous woman in the world and

Coogan, fresh off

Charlie Chaplin's "The Kid," was the hottest child star

in

Hollywood. Holland was most definitely "A-List."

Cecil also performed in a pair of Paramount pix called

"The Great

Impersonation" and "A Wise Fool." Cecil promoted himself

as "The Man of

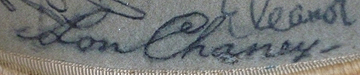

1000 Faces." I know. You think this was Lon

Chaney's monicker. And you're right. But not

until

Cecil gifted his pal with the title years later.

Lon Chaney

1922 brought roles in four more movies, with Holland

playing dual

characters in the best known of them, the Rudolph

Valentino vehicle

"Moran of the Lady Letty." This is the only Cecil

Holland

silent movie I was able to locate on DVD, and I can

report he was quite

a good actor, with an expressive face and considerable

"presence." And his dual make-up concoctions made

it

virtually impossible to tell it was the same actor

playing the parts -

a Mexican bandit and an old seaman who shanghais

Valentino.

Cecil

Holland (left) and Rudolph

Valentino in yachting cap (center)

in "Moran of the Lady Letty."

Also in

1922, the 35 year old Holland eloped with Norma

Taylor, 11

years his junior. To top off the year, Cecil

signed a

two-year contract with Samuel Goldwyn Pictures as a

stock player, while

continuing freelance make-up work all over town.

The media started

paying attention to Cecil Holland. There are

headlines from

this era in the "Los Angeles Times" entertainment pages

like "Wrinkles

in

Norma [Shearer]'s Face His Doings" and "Holland to Hand

Jack [Dempsey]

Black Eye." It's clear that if the LA Times had

speed dial in

those days, Holland's name and number would have been

next to the entry

for "story on movie make-up."

WELCOME

TO

M-G-M

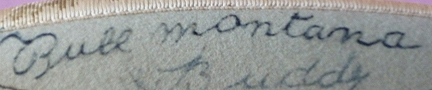

1925 was a watershed

year for Holland. He started off by transforming

Bull

Montana into an apeman - again - but this time for "The

Lost World,"

one of the best remembered of all silent movies.

Famous

wrestler

Bull Montana as an apeman in "The Lost World."

Cecil

making up Bull Montana for "The Lost World."

Bull

Montana

And

Holland

was then signed to an acting contract by one-year old

M-G-M. Simultaneously,

and

much more significantly, Cecil was hired by M-G-M

chief Louis B. Mayer to form a permanent make-up

department, the first

to exist at a major motion picture studio.

M-G-M

was a factory with films rolling off the assembly line

about once a

week. Having a make-up department that produced

consistent,

reliable, and even inspired make-up was an indispensable

part of the

mass-production process.

It is likely that one of Holland's first assignments at

M-G-M was the

gargantuan epic "Ben-Hur". Over 3,000 extras for

the

legendary

chariot race sequence were tended to by a small army of

make-up artists

using Max Factor body paint (at 600 gallons, it was

Factor's largest

order to date). And in addition to working his

magic on

famous faces and not so famous faces (M-G-M, like all

studios, was

constantly making screen tests of potential contract

players), Holland

had considerable administrative challenges - setting up

a permanent

make-up facility, hiring and training other make-up

artists, not to

mention analyzing the make-up needs of 50+ films and

shorts a year.

With those kinds of responsibilities (think of tending

to those famous

M-G-M stars - Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford,

John Gilbert,

Lillian Gish, Buster Keaton, Marion Davies, Renee

Adoree, Mae Murray,

Ramon Novarro! Norma Desmond was right; they

really did

have

faces then), it's not surprising that Cecil only had

time to appear in

small roles in two films during 1925 and 1926.

There was "The

Show," a goulash about a Hungarian carnival troupe

directed by Tod

Browning and "The Blackbird," starring Holland's good

friend Lon Chaney

(one can just imagine their conversations about

make-up).

A 1927 MGM advertisement featuring

some of their stars, almost-stars

and supporting players. Cecil is in the upper

right corner.

With some naked ladies around the border, this was

probably created for

exhibitors,

not the general public.

In

1927, Holland's wife gave birth to their daughter,

Margaret, joining

a son, Richard, who'd arrived a few years earlier, and

by then they

were

residing, with a live-in servant, in a hillside house

with a pool up on

Hazen Drive in the Coldwater Canyon section of Beverly

Hills. The house had a tunnel into the mountain

which led to

a secret barroom (the influence of Prohibition on

interior

design?).

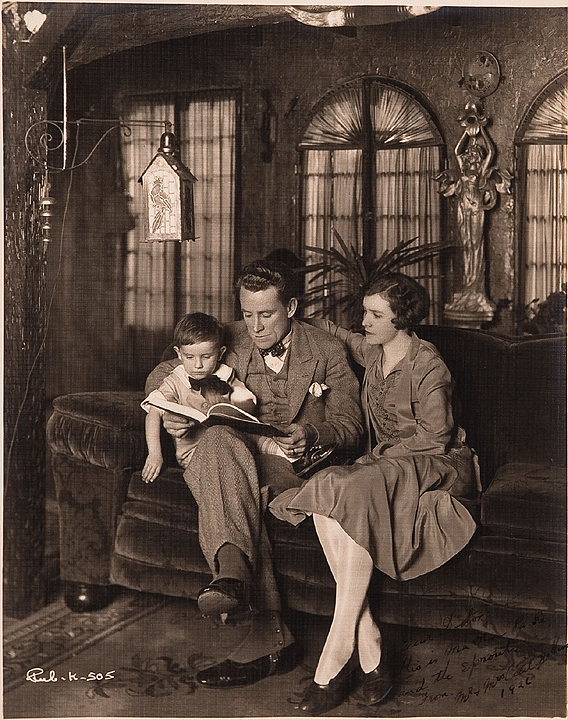

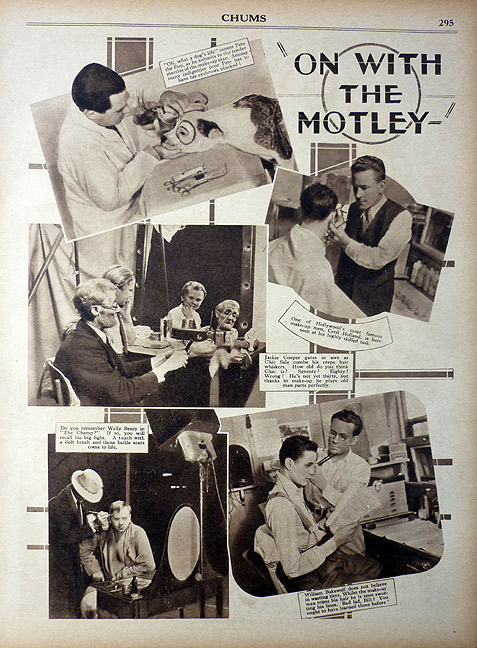

Richard, Cecil

and Norma Holland at home.

Check out those spats Cecil is wearing.

The

Holland

house was filled with mementos picked up on

Cecil's world

travels.

The

Holland

house was filled with mementos picked up on

Cecil's world

travels.

Cecil

Holland,

circa 1926, thanks to an

M-G-M publicity still.

The house is quintessential 1920's - filled

with velvet furniture, dark walls,

and

heavy curtains to keep out the California sunlight.

THE

ART

OF MAKE-UP

This

was also the year when Cecil

decided to

capitalize on his official M-G-M title - Director of

Make-Up. We

all know

"self-promotion" is the lifeblood of Los Angeles.

It must be

something in the water out here. Cecil had a plan

to open a

school for aspiring make-up artists. And to make

himself

known to those wannabes beyond the small world of

Hollywood, he wrote

the very first book on movie make-up, a slim hardcover

volume of not

much more

than 100 pages called The

Art

of Make-Up for Stage & Screen.

Cecil

Holland wrote the

first book ever written on the art of movie make-up.

The

book's first pages are devoted to lengthy

testimonials,

swearing to Holland's prodigious talents, signed by Mary

Pickford,

Douglas Fairbanks, Norma Shearer and John Gilbert, among

others. To top that, there's an erudite preface

written by

Lon Chaney that stresses Holland's quarter of a century

experience as

an

actor; Chaney assures the reader that Cecil knows his

stuff.

The fact that Cecil is the Director of Make-Up

at M-G-M is

mentioned frequently. Holland understood the

concept of

"branding" before there was a name for it.

The

book is jam-packed with the "how-to" for everything from

"straightening" a nose through make-up to the skinny on

beards,

wrinkles, harelips and looking Asian (a Holland

specialty).

By way of illustration, the book is peppered with

full-page portraits

of Holland in a dozen disguises - The Fisherman, The

Drunkard, The

Pirate, The Clown, The Witch, the Chinaman, the Sheik,

and, most

startlingly, as Jesus backlit with a heavenly halo --

many of which

were

used in his M-G-M composite picture.

All nine of the characters in this 1925 M-G-M

composite are Cecil

Holland,

the original "Man of 1,000 Faces."

Cecil Holland as You Know Who

There are

lots of little tricks revealed, one of the most

surprising being that

to

replicate the look of a blind man with milky white where

the eyeball

should be, cover the actor's eyeball with the

translucent inner skin of

an eggshell. Holland had used this trick on an

actor named

Raymond Bloomer back in "The Love Light" in 1921, and

Lon Chaney

reputedly used it in "The Road to Mandalay" in 1926.

The Art of

Make-up ends with a list of Max Factor products

every

make-up artist

should have, including Grease Paint Tubes and Liquid

Body Make-Up in

many shades including Mikado (I'm guessing this is an

artful euphemism

for

Asian). There's also a glossary of non-cosmetic

products a

make-up artist needs to keep in his "toolbox" for

transforming facial

features - mortician's Plasto wax, flexible and

non-flexible Collodion

(used for "new skin" and "scarred skin"), guttapercha

(dentist's used

this for temporary fillings), fish skin (a medical

product useful for

pulling the skin and making Caucasian eyes look

Asian). I

asked make-up artist Roy Helland (who's won an

Oscar and an

Emmy doing hair and make-up for Meryl Streep for 30

years, so he knows

a thing or two hundred about transformative make-up) if,

85 years

later, these were non-cosmetic products you could still

find today, and

he said "Yes. In a museum."

TALK.

TALK.

TALK.

I can't find any record of Cecil's School of Make-Up

opening, so

it may have been a time-management casualty of the

arrival of

Talkies. The upheaval caused by going from silent

pictures to

sound pictures wasn't just about which star had a

mellifluous voice; it

also greatly affected the technical aspects of

filmmaking, including

movie make-up. Silents were shot with noisy carbon

lights.

Adding microphones to a movie set necessitated a switch

to quiet

tungsten lights. But, the orthochromatic film that

had been

used since the early Teens wasn't sensitive enough to

clearly record

images with the new lighting. An industry-wide

change to

panchromatic film occurred. Panchromatic film

required much

more light -- "end-of-the-world-with-a-bang" kind of

light, to be

precise. And more light required a new approach to

make-up

and make-up application - different make-up, less

make-up, different

shades and much more thinly applied.

Replacing the actors who didn't make the switch to sound

were a raft of

new M-G-M stars - Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, Jean

Harlow! And,

during this transition period, Cecil made his final

appearance in a

film - a cameo, if you will - in his one and only talkie

- "Mata Hari,"

filmed in 1931. The script called for Greta Garbo

to ask a

question of a blinded WWI soldier during a hospital

visit to her lover,

Ramon Novarro. Cecil, using the old egg shell skin

trick,

played the part himself.

Hello,

Greta.

Goodbye, Silver Screen.

Cecil Holland's last film role is a blind soldier

who has a brief encounter with Greta Garbo in 1931's

"Mata Hari."

Holland

is very affecting in the

"Mata Hari" scene, exhibiting a serene and still

demeanor and speaking

in a tenor-ish voice with a mid-Atlantic accent.

From his

years on stage, he was very adept at accents, so there's

no way of

knowing if this was his off-screen voice, too. And

if you

have a swan song in moving pictures, there are worse

ways to do it than

playing a scene with Greta Garbo in her prime.

Around this same time, Cecil was developing extensive

make-up for Helen

Hayes in "The Sin of Madelon Claudet," the hoariest

story of mother

love ever put on the screen (it makes "Stella Dallas"

and "Madame X"

look like episodes of "Modern Family.") Hayes has

to age over

30 years in this saga of a sweet young thing who is

abandoned by her

fiancee, gives birth out of wedlock, is thrown out by

her father,

marries an older man who turns out to be a jewel thief,

is sentenced to

10 years in prison although she's committed no crime,

and then turns to

prostitution and petty thievery to not only survive but

pay for her

estranged son's medical school studies. Are you

seeing all of

the amazing make-up opportunities here? Holland

did, and gave

Hayes a half dozen realistic looks as she inexorably

slid down the

rungs of the social ladder. Of course the film was

a huge hit

and won Hayes the Best Actress Oscar for 1931-32.

Cecil

helped her win that Academy Award in the same way the

creator of the

Virginia Woolf nose helped Nicole Kidman win her Oscar

for "The Hours."

A week or so after the film's premiere, Hayes wrote

Holland:

Dear

Cecil

Holland

Our

nightmare

of last summer has turned out to be a triumphant

picture here

in New York. I have received great praise for

my masterful

makeup. It makes me feel guilty, so I hereby

forward that

praise to you, where it belongs. I'm ever so

grateful for

your patience and artistry.

God

bless

and good luck.

Helen

Hayes

Helen

Hayes

Helen

Hayes

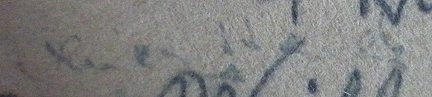

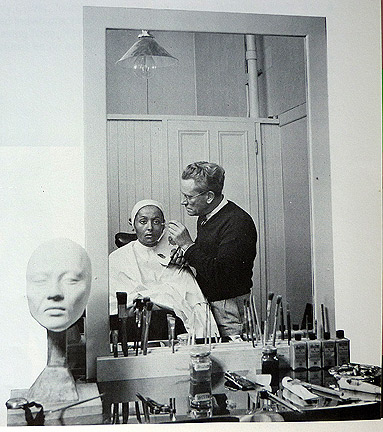

A feature on Hollywood make-up appeared in

"Chums," a British magazine

for boys,

in 1932 with two pictures on the right of Holland at

work.

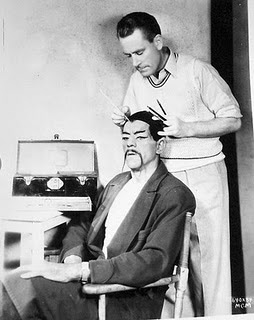

Pictures by such eminent M-G-M staff photographers as

Clarence Bull had

been taken of Cecil at work as early as his first year

at the

studio. There are photos memorializing him

finishing out an

eyebrow for Joan Crawford in 1928's "Our Dancing

Daughters" (the silent

film that rocketed her to stardom); of drawing the

circle around the

eye of Pete the dog from the Our Gang comedies; of

examining his

creation of the grenade-caused scars on the right side

of Lewis Stone's

face in "Grand Hotel"; and of making Boris Karloff look

sinister and Asian for the 1932 "The Mask of Fu Manchu."

(Karloff lived

next door to Holland, and his co-star, Myrna Loy,

moved in just around the corner several years later --

Who says

Hollywood isn't a small town?) In all of the

photographs, Cecil expertly plays the part of the

focused and serious

make-up artist, allowing the "star" to be the true

center of attention.

Cecil Holland working his magic on the eyes of

Joan Crawford

for 1928's "Our Dancing Daughters."

Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford

Drawing the circle around the eye of Pete the dog

for the "Our Gang"

films.

Applying final touches to the war wounds on the

face of Lewis Stone for

"Grand Hotel,"

under the watchful eye of director Edmund Goulding.

Lewis

Stone,

remembered best for playing Judge Hardy in the Andy

Hardy series

of films, also uttered one of the best-remembered

closing lines in a

movie:

"Grand Hotel. People come. People go.

Nothing ever happens."

Stone was a contract player at M-G-M from its

inception in 1924 until

his death in 1953 -- the longest-known uninterrupted

association of an

actor and a

studio.

Lewis

Stone

Turning

Boris

Karloff Asian (and sinister) for "The Mask of Fu

Manchu."

Boris

Karloff

Also

from 1932 is a

picture of Holland using a magnifying loupe to check

out the

just-finished maquillage of Jean Harlow at her most

"platinum," while

she sits in a barber's chair dressed in a polka dot

wrapper and

Spring-o-later-style pumps. I love this

picture.

It's set in what is clearly Cecil's "office." On

the wall is

a picture of him with wife Norma and their son, a copy

of Holland's

1925 composite pic and a bevy of framed portraits of

him in character

make-up. Center stage is the

photograph of Holland as Jesus, which is flanked by

smaller pictures of

Cecil's parents (I wouldn't touch the symbolism of

that with a 10 foot

long tube of lipstick). But, all of the

reminders of

his former career don't seem like a desperate

attempt at hanging on to the glory days. They

were visual

substitutes for Holland saying to those who sat in his

make-up

chair: "Hey. Relax. I'm just like

you. I understand what it's like to be an

actor.

So, sit back and don't worry; I'll make you look

your

best."

Jean Harlow under the Master's gaze.

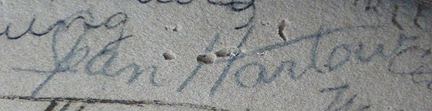

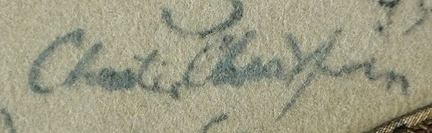

SHAW

GOES

HOLLYWOOD

As

mentioned earlier,

one of the most stunning discoveries while deciphering

the names on the

hat was that of George Bernard Shaw. In 1933,

world-renowned

playwright and Nobel laureate Shaw visited the United

States for the

only time in his life. Accompanied by his wife,

Charlotte,

Shaw was on a year long cruise around the world and got

off his ship,

The Empress of Britain, in San Francisco and went down

the coast to

spend a night at William Randolph Hearst's fabled

estate, San

Simeon. On the morning of March 28, Hearst

instructed his pilot to fly the Shaws down to the Santa

Monica airport

in Hearst's private plane. The pilot was bedeviled

by thick,

low coastal fog, and knowing that he'd never find the

airport, made an

emergency landing on the sands of Malibu beach.

Unperturbed,

the Shaws hitchhiked a ride from a passing UCLA student

who dropped

them off at the airport, where they were met by Louis B.

Mayer and a

phalanx of his underlings.

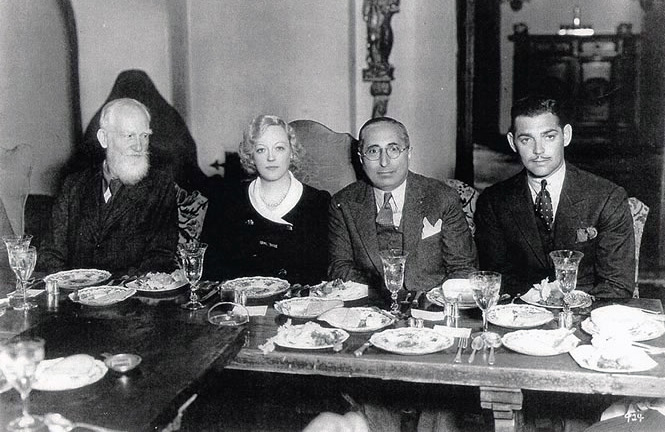

George Bernard Shaw with Marion Davies, Louis B.

Mayer and Clark Gable.

Why is nobody having a good time at this lunch?

Once at M-G-M in

nearby Culver City, the Shaws were given an exuberant

tour of the lot

by Cecil Holland. Louis B. Mayer chose Holland

because, like

Shaw, he was a Brit, and he assumed the regional

connection would make

for a smooth hour. The hour must have been just

fine, because

Shaw did sign "the Hollywood Hat." But the rest of

the three

hour visit seems to have gone south. Shaw insulted

many of

those he encountered -- reporters, actors and, judging

by the dour

expressions in the picture above, most, if not all, of

his companions at lunch. The luncheon was hosted by

Marion Davies in her 16 room

"bungalow" dressing room. The guest list included Mayer,

Charlie Chaplin,

Clark Gable and John Barrymore, to whom Shaw refused an

autograph. Shaw was definitely Mr. Nastypants that

day before

heading back to his ship. For the next week, the

Los Angeles

newspapers' chatter and gossip columns were filled with

civic umbrage

and the provincial equivalent of "who does he think he

is?"

Shaw certainly knew how to make an impression.

Marion Davies

|

John Barrymore

|

CHANGE

PARTNERS

After a decade at M-G-M, Holland was ready for a

change. He

was almost 50 (do I hear the phrase "mid-life crisis" in

the house?)

and almost certainly tired of all of the administrative

duties that

came with being the head of the Make-Up

Department. Cecil

loved doing make-up and teaching make-up, not filling

out forms about

make-up. M-G-M's success was also Holland's

success. He stood at the absolute pinnacle of his

profession,

and decided to cash in while giving himself new

challenges.

Cecil did what almost no one in the film business did in

1935; he gave

up a sure-thing contract in the middle of The Great

Depression and went

on to free-lance with a series of short-term, and no

doubt lucrative

assignments.

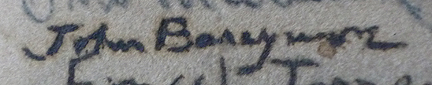

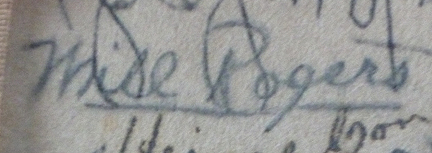

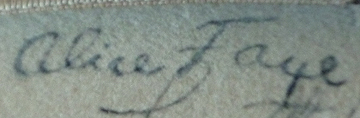

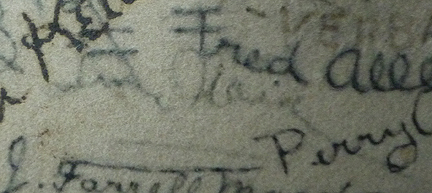

In 1935, Holland first went to newly-formed 20th Century

Fox, the

hottest

studio in town, and unpacked his make-up box.

Among the stars

he worked on was Shirley Temple, then the biggest draw

in the

movies. And, while there, he got lots more

signatures on "The

Hollywood Hat" from folks who sat in his chair - among

them, Alice

Faye, Will

Rogers, Sonja Henie, and Cesar Romero.

Will Rogers

|

Alice Faye

|

Sonja

Henie

Sonja

Henie

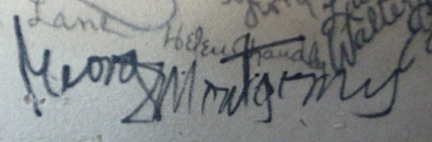

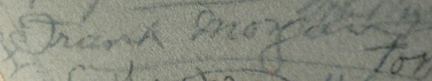

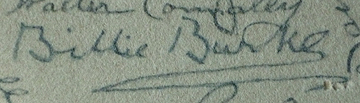

This appears to be where the hat was finally "filled

up." You

can

tell because many of the signatures he only could have

gotten at 20th

are small and appear in those leftover areas of the hat

between big

signatures. The penultimate addition to the hat --

at least

four

years later -- is actor George

Montgomery, who signed the hat twice, including once

where the hatband

used to be. Born George Montgomery Letz, he didn't

go by

"George Montgomery" until 1940, when he was put under

contract by Fox.

Both Montgomery and Holland shared painting and

sculpting as

hobbies, and I suspect they bonded over these mutual

interests, enough

for Holland to pull the hat out of the closet and have

George sign it.

George Montgomery

When M-G-M started "The Good Earth" in 1936, Jack Dawn,

now the head of

M-G-M's Make-Up Department, hired back Cecil for his

expertise to

transform decidedly Caucasian Luise Rainer into Asian

O-lan, the female

lead character. Dawn worked on the male lead, Paul

Muni.

Why not cast Asians and save a lot of

trouble?

Well, with a $2 million dollar budget (six or seven

times the typical

M-G-M budget at this time), the film's producer, Irving

Thalberg,

insisted on box office names. And there simply

were no Asian

box office names in 1936.

Transforming Luise Rainer into the Chinese farmer's

wife, O-lan,

for

"The Good Earth" in 1936.

Production took up

much of 1936, and Holland and Rainer had one colossal

disagreement. Luise wanted her fingernails

manicured. Cecil not only wanted them unpolished,

he wanted

to put dirt underneath the nails. After all, she

was a

farmer's wife, not a shopgirl in a Peking

emporium. Cecil won

this battle in the name of authenticity, and Rainer won

her second

consecutive Oscar for Best Actress.

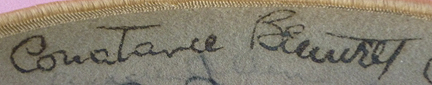

In March, 1937, Holland interrupted his free-lancing and

agreed to head

up the Make-Up Department at the Hal Roach Studios. It

was at this

exact point in time that Roach switched the studio's

emphasis from

comedy shorts to A-List features, such as "Topper" with

Cary Grant and

Constance Bennett. It was also in 1937 that a

decade-long

quest of Holland's finally ended. In the late

1920's,

Holland, along with other noted make-up artists and hair

stylists,

formed the "Hollywood Motion Picture Make-Up Artists

Association" as a

first attempt to unionize their profession and affiliate

with organized

labor. It took them five years to find a home, and

it was

first with the painters' union; the logic being that

both groups'

workers used brushes. Finally, in 1937, IATSE,

which

controlled most of the unions in Hollywood, relented and

gave a charter

to the make-up artists and hair stylists; Local 706 was

born.

Cecil didn't stay at Roach very long; in the summer of

1938, he was

called again by Dawn at M-G-M with a irresistible offer

to work on the

much anticipated "The Wizard of Oz" (talk about

character make-up) and

he finished out the 1930's on the Yellow

Brick Road. "The Wizard of Oz" was such a huge make-up

and hair

operation that the prep area filled an entire

soundstage.

Frank Morgan

|

Billie Burke

|

The 1940's was a period of active free-lancing for

Holland with stints

at 20th and Warner Brothers, among others. For

most of the

decade, there

are no credits for Holland that I can find (and Local

706 no longer has

work records from this period). The practice

during the 40's

was to give the head of the Make-Up Department the

screen credit, if

the credit was mentioned at all. An individual who

worked in

the Department, whether under contract or as a

free-lancer, was

invisible. Holland started a sideline business

doing oil

portraits, and one of his commissions was painting the

pet of Betty

Grable and bandleader Harry James. I'm not sure if

this

happened because of knowing Grable at 20th or from Betty

and Harry

being Cecil's nearby neighbors.

Cecil appears to have finished out his career mostly

working at Republic

Pictures. Holland got screen credit for the

make-up on 1949's

"The Fighting Kentuckian" starring John Wayne, and then

"Borderline" in

1950, a "tense" drama with Fred MacMurray and Claire

Trevor.

1951 saw Cecil's last notable (though uncredited)

achievement in movie

make-up. This came about via Lee Greenway, one of

his former

interns when both were at 20th in the 1930s.

Greenway is most

famous for creating the alien monster make-up worn by

James Arness in

"The Thing From Another World," produced by Howard Hawks

at R-K-O.

Greenway didn't have the hours each day to apply

Arness'

make-up, so he hired "Teach" for the task.

Undoubtedly,

Holland and Arness became close during the weeks of

filming.

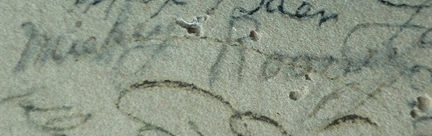

James Arness was the last person to sign "The

Hollywood Hat."

James

Arness

James

Arness

Having

reached what may have been mandatory retirement age in

1953, Holland

left

make-up work for good and turned his attention to his

other artistic

pursuits.

In 1965, at the age of 78, Cecil suffered a paralytic

stroke.

After extensive therapy, he still had trouble with

speech.

Apparently, when the

ability to express the right words failed him, Cecil

reverted back 50

years, and, as in his silent movies, he would act out

what he wanted to

say. In 1973, he was beset by another stroke,

complicated by

pneumonia. This proved to be too much for him, and

Cecil

Holland died in Sherman Oaks on June 29, just one month

after his 86th

birthday.

Cecil left a 40 year legacy of dozens of films in which

he acted and

hundreds of films for which he created the

make-up. More

importantly, for four decades, he had generously and

eagerly shared his

vast knowledge with other make-up artists, training

countless

individuals in the complex and fine art of creating

make-up illusions

and beauty (come to think of it, sometimes beauty IS a

make-up

illusion.)

And Cecil left behind "The Hollywood Hat."

A

WINDOW INTO HOLLYWOOD

For me, the hat is a series of windows

into Hollywood and all those who

signed it when the movies first talked. But it was

much more

than that for Holland. His daughter, Meg, says it

was his

"pride and joy." That's a good start. By the

time

Cecil got to M-G-M, he'd been to the fair and he'd been

around the

block (hell, he'd been around Cape Horn in stormy

seas). It's

a certainty that he recognized that being the Director

of Make-Up at

the biggest, richest, most glamourous and successful

studio in

Hollywood was "It." These were the best years of

his

professional life, and he loved most every minute of

it. What

better way to memorialize the daily joy than to get

autographs of

everyone meaningful to sit in his make-up chair, and to

have all the

signatures in one place - on the hat? It's not

that different

than a high school yearbook where your best friends pick

up a pen and

leave a little piece of themselves for you to remember

them by.

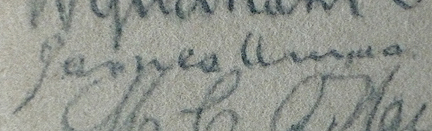

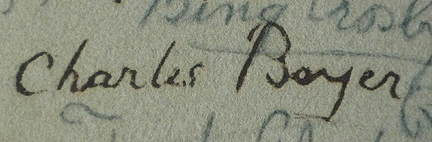

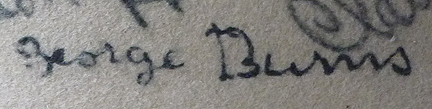

Studios are just like small towns -- with couples who

are married, like

Charles Boyer and actress Pat Paterson ...

Charles Boyer and wife Pat Paterson

on board the

French luxury liner Normandie in the

late 1930's. After 44 years of marriage,

Pat died.

Boyer, unable to face life without her,

committed suicide two days later.

Charles Boyer

Pat Paterson

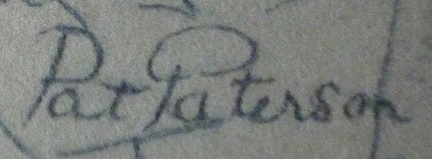

George Burns and Gracie Allen ...

When George Burns and Gracie Allen started

their

vaudeville act in the early 1920's,

George played the illogical character and Gracie

was the "straight

man." Her signature

may have faded on the hat, but thank goodness

the memory of her

whimsical comedy hasn't.

George Burns

Gracie Allen

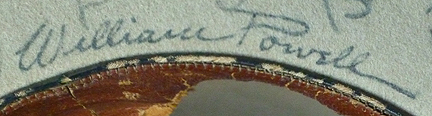

and couples the public thought should

be married, like William Powell

and Myrna Loy ...

William Powell and Myrna Loy made a whopping 14

movies together.

During the time they made these movies, they

were married to others a

total of 5 times,

but never to each other. Asta, played by a

wire-haired fox

terrier named Skippy,

was their co-star in the popular "The Thin Man"

series. Alas,

Skippy didn't make

a paw print on the hat.

William Powell

Myrna Loy

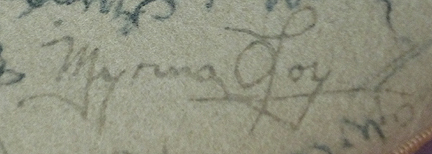

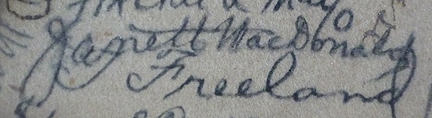

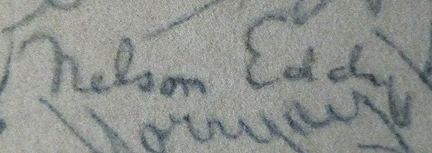

and Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy.

If Nelson Eddy had his way, he and

Jeanette

MacDonald would have been married in real life.

During much of the time they were teamed on 8

musicals, the two had an

on-again,

off-again romance, with Eddy pressuring

MacDonald to marry him and give

up her career.

Jeanette MacDonald

Nelson Eddy

CECIL

AND

"THE KING"

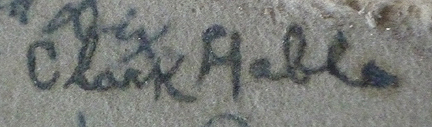

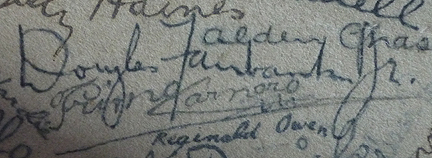

There are two great publicity

photographs M-G-M took of Holland in 1932. One is

of Cecil

and Clark

Gable on the staircase in the back of the dressing room

building.

Gable has the hat with his hand holding a pen at

precisely the place on

the hat where he signed it. M-G-M's caption says

there are

over 2,000

signatures on the hat which is typical Hollywood

hyperbole; there were

probably no more than 250 at the time. Gable is

looking at

Holland,

but Holland is looking at the hat.

Clark

Gable

autographing

the

hat.

Clark

Gable

autographing

the

hat.

Provenance doesn't get any better than this.

Clark Gable

The

other photograph is of Cecil

alone, wearing the hat, with a vast expanse of the

underbrim still to

be filled in. The camera catches him with a

Cheshire cat

smile. He

is clearly proud to be wearing this hat. (And, on

an

interesting

sartorial note, he's wearing a collar pin, a tie tac and

a tiebar.)

Cecil Holland sporting his "pride

& joy," October 1932.

Once "complete," the

hat was stored in Cecil's foyer

closet on Hazen Drive. His family says that

Holland would

often take it out of the closet and show it off to

company.

Although it wasn't yet a dazzling historical pop culture

artifact, I'm

sure it sparkled plenty when the names were still

current.

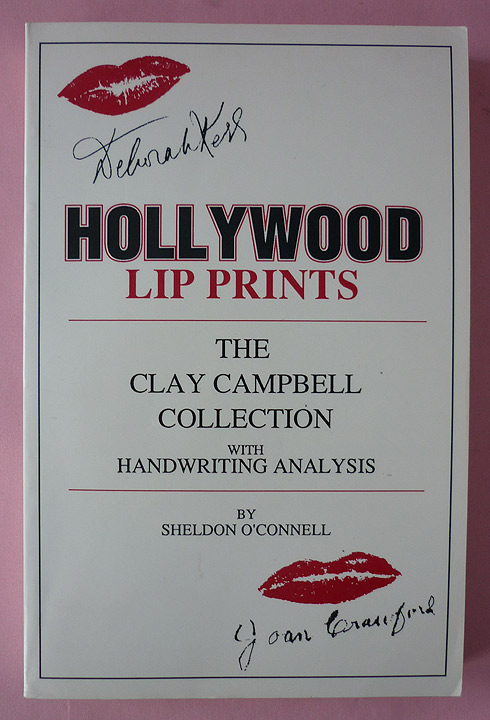

By the way, Holland wasn't the only make-up artist to

have an unusual

way of collecting autographs. Clay Campbell, who

spent 33

years as a make-up artist, most of those years heading

Columbia

Pictures' Make-Up Department, had over two thousand of

the actresses he

beautified put their fresh lip imprints on pieces of

paper and then

sign them.

Hollywood Lip

Prints

Sheldon O'Connell's book about Clay Campbell's collection

of 2,000 lip

prints

George Westmore, the patriarch of multi-generations of

make-up artists

(his sons, at one time or another, ran practically every

major studio

make-up department) also collected about 100 autographs

in a small

leather-bound album. It was available in the

December, 2011

Debbie Reynolds auction, and, even in terrible condition

- water

damage, loose pages, etc. - it sold for more than

$3,000. An

interesting piece of trivia is that when M-G-M sent

Cecil Holland to

England on studio business for a few months in 1929,

George Westmore

was his temporary replacement as the Director of Make-Up

at M-G-M.

And the hat wasn't Cecil's only experience with

autographs.

During World War I, he'd been contacted by a British

women's service

organization, requesting signed movie star pictures to

cheer up wounded

veterans. He assembled over 100 of them and

shipped them off

to England. And, a few years ago, a hardbound copy

of "The

Wizard of Oz" came up for auction in England. It

had been

signed by all the principal cast members of the 1939

movie, and the

auction catalog noted that the book had been a gift to

the consigner's

great-grandfather, a friend of Cecil Holland, who had

the book signed

during production of the film. The book sold for

the

equivalent of $10,000.

Cecil had the cast sign this copy of "The

Wizard

of Oz" as a

gift for a friend,

which, 70 years later, sold at auction for $10,000.

THE

DEMOGRAPHICS

OF THE HAT

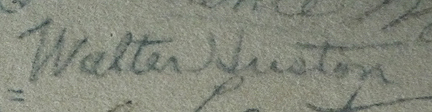

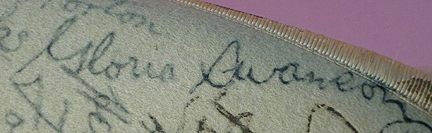

The "demographics" of the hat tell us a lot about

Holland,

too. 80% of the signers are men and only 20% of

the signers

are woman. It's not that Cecil couldn't do beauty

and glamour

(Gloria Swanson, Jeanette MacDonald, Joan Crawford - and

they weren't

playing stay-at-home Moms in housecoats and curlers),

but he

found working

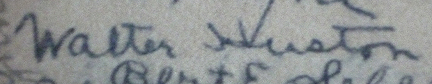

on actors more rewarding. Walter Huston once

inscribed a

photo to Cecil which called him "God's gift to character

actors." Such were Holland's talents at painting

character on

a face that I think that's where he spent most of his

time.

The hat is filled with the names of dozens and dozens of

character

actors. The names might not be familiar, but the

moment you

see their picture, the response is "Oh, that guy.

I've seen

him in a hundred movies."

It's also interesting

to realize who, among the M-G-M stars Cecil worked on,

didn't sign the

hat. For one, there's Greta Garbo, which isn't a

shock. Garbo famously signed almost nothing but

checks and

contracts. In the 1995 book "Garbo" by Barry

Paris, he

relates Greta's response to the thousands of fan letters

that arrived

every week at M-G-M, and which were burned,

unread:

"Who are all these people who write? I don't know

them. They don't know me. What have we to

write

each other about? Why do they want my

picture? I'm

not their relative." A hilarious response.

And

astute. And very practical.

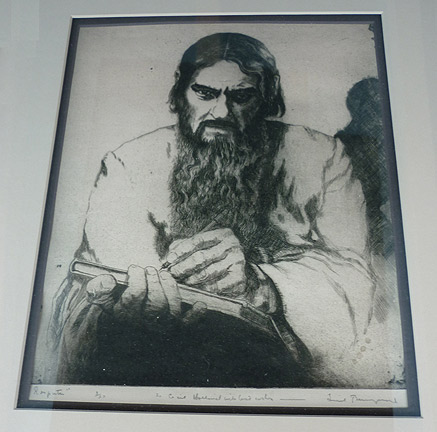

Lionel

Barrymore as Rasputin in "Rasputin and the Empress."

Make-up by Cecil Holland. Barrymore did the

etching himself

and gave it to Holland at the end of the shoot. For

whatever reason,

Lionel Barrymore never signed the hat.

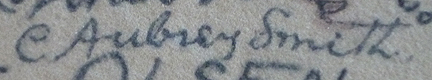

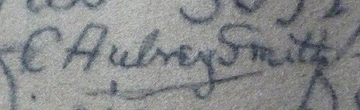

Eight years is a long

time to collect autographs and Cecil mistakenly had some

sign the hat

twice, including character actors Walter Huston, Lee

Tracy, Conrad

Nagel, C. Aubrey Smith, and Roland Young, as well

as the

platinum bombshell herself, Jean Harlow. The

Harlow

signatures may be the rarest on the hat. She was

very shy

around her fans and rarely signed in-person

autographs. And

it is well-known in the autograph community that

virtually all of the

signed photographs of Harlow now floating around were

actually signed

by her mother, Mama Jean.

Walter Huston 1

|

Walter Huston 2

|

C. Aubrey Smith 1

|

C. Aubrey Smith 2

|

Jean Harlow 1

|

Jean Harlow 2

|

THE

DEMOGRAPHICS

OF FAME

The "demographics" of fame

as represented by the names who signed the

hat are fascinating. "Lasting fame" is measured in

different

ways in Hollywood. Foremost is earning an Oscar

nomination

or, better yet, the statuette itself. Every Oscar

winner

knows that the lead sentence in his or her obituary will

read something

like this:

"Tonight, Oscar winner ________________ died in

___________________ (choose one: Cedars

Sinai Hospital/St. John's Hospital/at home) after a

___________________(choose one: long battle/short

battle) with

_________________ (choose one: cancer/substance

abuse/Jeffrey

Katzenberg)."

The Academy Award is simply the universal emblem of

achievement in the

film business. Nothing else comes close.

Among the signers of the hat, there are 60 individuals

who were

nominated for an Oscar 134 times. And there are 31

winners of

Oscars

(reaping a total of 41 Academy Awards), including the

cranky George

Bernard Shaw (screenplay for "Pygmalion," 1938).

Shaw

publicly pooh-poohed the award, but kept his Oscar

prominently

displayed on his mantel for the remainder of his life.

Even more exclusive than the Oscars is the forecourt of

Grauman's

Chinese Theatre, filled with the hand and foot prints of

Hollywood

immortals. A couple of thousand Oscars have been

handed out,

but there are only about 250 stars represented at

Grauman's.

(I'd give

you an exact number, but do you count or not count R2D2,

C3PO and Roy

Rogers' horse Trigger?) There are a variety of

stories of

how the footprints ceremonies began, but most agree

Norma Talmadge was

the first to get cement on her hands and shoes in

1927. Since then, there have only been an average

of three

stars added each year. Like I said, exclusive.

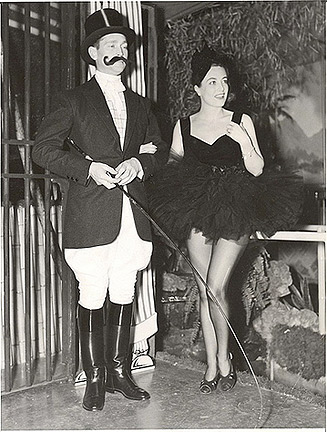

Four

lady

hat signers at one of Marion Davies' many costume

parties:

Gloria

Swanson, Marion Davies, Constance Bennett and Jean

Harlow.

The

three dressed in "Heidi" gear also have their foot and

hand prints

Four

lady

hat signers at one of Marion Davies' many costume

parties:

Gloria

Swanson, Marion Davies, Constance Bennett and Jean

Harlow.

The

three dressed in "Heidi" gear also have their foot and

hand prints

at Grauman's Chinese Theatre.

Gloria Swanson

|

Constance Bennett

|

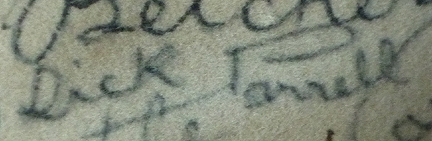

Married

couple Dick

Powell and Joan Blondell jointly leave their hand and

foot prints at

Grauman's

Married

couple Dick

Powell and Joan Blondell jointly leave their hand and

foot prints at

Grauman's

Chinese theater in February, 1937. The man

assisting them is

Jean Klossner, who created the

extra-durable concrete used in the forecourt and who

supervised the

footprint ceremonies

from 1927-1957. He was known as "Mr. Footprints."

Dick Powell

Dick Powell

Joan

Blondell

Eddie

Cantor was an enormously popular film star in the early

1930's and is

shown here,

Eddie

Cantor was an enormously popular film star in the early

1930's and is

shown here,

putting his Best Foot Forward at Grauman's in 1932.

Eddie Cantor

Eddie Cantor

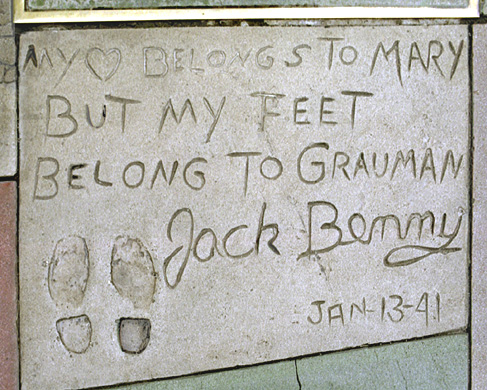

Jack

Benny's cement block at Grauman's Chinese Theater.

Jack

Benny's cement block at Grauman's Chinese Theater.

He wrote so much verbiage there was no room for hand

prints.

Jack Benny

Jack Benny

Of

those 250 stars, how many of them

autographed "The Hollywood Hat"?

A whopping

39. Or almost one out of every six.

Starting in

1932, Quigley Publications, a reputable motion

picture

trade publisher, annually polls theater owners for a

list of which ten

stars' movies brought in the most customers.

It's not the

most scientific way to judge box office success, but

the list is always

generally credible and it's endured for over 80

years.

Inclusion

on the list is also often mentioned in a star's

obituary.

From 1932

to 1939, thirty-three stars appeared on the Top Ten

Box Office Stars

list (clearly lots of repeats from year to

year). Of those, twenty-one autographed "The

Hollywood Hat."

That's more

than 60%.

Joan

Crawford was

a mainstay of the Top Ten Box Office Stars List in its

first years.

An amazing number

of hat signers

appeared in Crawford movies, including her first two

husbands,

shown here with Joan in

Fancy Dress Ball

costumes.

On the left, husband #1, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

On the right, husband #2,

Franchot Tone.

Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

Franchot Tone

WATCH

WHERE

YOU STEP

Then there's the Hollywood Walk of

Fame, represented by all those

glittery pink stars lining Hollywood

Boulevard. When

Hollywood (the neighborhood) started to decline in

the early 1950's,

E. M. Stuart, a civic booster, came up with the idea

of installing the

sidewalk stars as a way to goose tourism. Four

committees

were formed to create lists of those worthy of a

star in any of four

areas - films, television, radio and records/music.

People

could be awarded more than one star if they had

excelled in more than one medium.

Ultimately,

1550 stars were initially awarded. The list

was

not without controversy. Charlie Chaplin's son

unsuccessfully

sued the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce for $400,000

for the omission of

his father's name. Apparently, to some, in the

tail end of

the McCarthy era, Chaplin's leftish worldview was

more meaningful than

the fact that Charlie Chaplin, the actor, had done

more to popularize

movies than anyone else in history (ps: he finally

got a star in 1972).

Charlie Chaplin

By

1961, the original stars had been

installed, and starting in 1968,

other stars were added to the Walk. About two

dozen, more or

less, have been added each year, until the total is

now close to 2500

stars. In 1984, a 5th category was added -

Theatre/Live

Appearances. It's also evolved into an honor

with a price

tag; the chosen star (or an entity acting on the

star's behalf) needs

to fork up some serious dough (currently about

$30,000) to underwrite

the cost of the installation, ceremony and future

maintenance. It's not unlike buying a plot in

a

cemetery. Both offer eternal remembrance, if

not salvation.

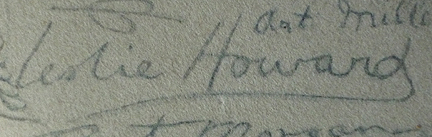

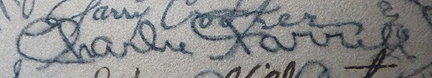

BOYS'

NIGHT

OUT

BOYS'

NIGHT

OUT

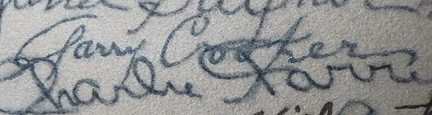

These

three very different leading men --

Leslie Howard, Gary Cooper, and Charles Farrell

--

all have sidewalk stars.

Leslie Howard

Gary Cooper

Charles Farrell

So

how did the hat signers do with the

Hollywood Walk of

Fame? 154 of them

(that's about 40% of those who signed

the hat)

are represented on the Hollywood Walk

of

Fame with 198 stars. That's a lot of sidewalk

sparkle.

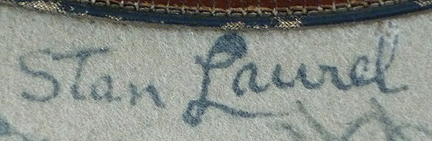

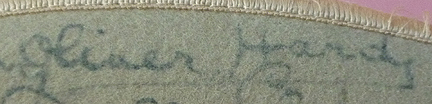

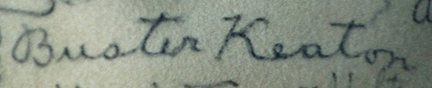

Comedy

Stars -- and Sidewalk Stars --

Stan Laurel, Buster Keaton, Oliver Hardy and

Jimmy Durante

all at M-G-M in the early 1930's.

Stan Laurel

Oliver Hardy

Buster Keaton

Jimmy Durante

It

might be tempting to put the Golden

Globes on this list as a

measurement of lasting fame, but the Globes only

started in 1943, a

decade after the era of "The Hollywood Hat."

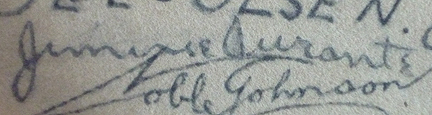

But, there was

something in the 20's and 30's as artificial and

manufactured as the

Golden Globes. It was called WAMPAS Baby

Stars.

WAMPAS

stands for Western Association of Motion Picture

Advertisers, a

trade group of film publicists and

advertisers. Starting in

1922, the group would annually identify 13 young

actresses who were on

the cusp of stardom. They didn't call them

starlets then;

they nicknamed them "Baby Stars." Given that

publicists

created this thing, there was a huge amount of media

attention given to

the announcements - newspaper articles, newsreel

footage, personal

appearances - and being a WAMPAS Baby Star turned

out to be a big deal

at that time.

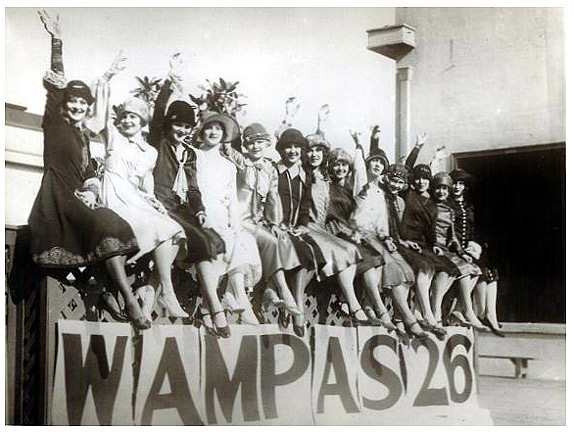

The

WAMPAS Baby

Stars of 1926.

From left to right: Dolores Costello,

Vera Reynolds,

Mary

Astor,

Marceline Day, Edna Marion, Mary Bryan,

Fay Wray, Janet Gaynor, Sally

Long, Joyce Compton, Dolores Del Rio,

Sally O'Neil, and last, but certainly not least,

Joan Crawford.

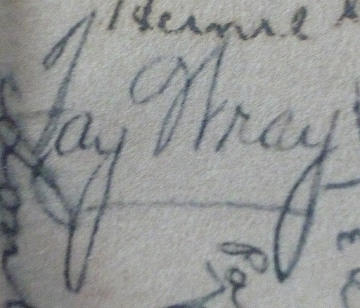

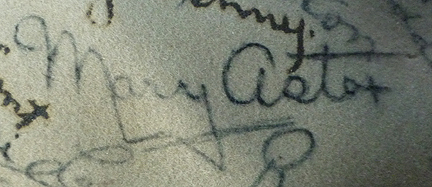

Fay Wray

Fay Wray

Mary Astor

Mary Astor

The

WAMPAS

group had a

pretty good track record of predicting stardom.

Among their

picks were Clara Bow, Bessie Love, Colleen Moore,

Dolores Del Rio, Jean

Arthur, Loretta Young and Ginger Rogers. Twelve

of the ladies

who autographed "The Hollywood Hat" were WAMPAS Baby

Stars including 5

from 1926 alone - Mary Astor, Marceline Day, Janet

Gaynor, Fay Wray and

the biggest Baby Star of all, Joan Crawford. The

awards ended

after the 1934 announcements due to studio pressure;

the moguls didn't

want anybody else telling them who should be a

star. The

crust of those publicists.

Cecil

turns glamour girl and 1928 WAMPAS Baby Star Gwen Lee

into

Cecil

turns glamour girl and 1928 WAMPAS Baby Star Gwen Lee

into

a Halloween

version of Pippi Longstocking.

It's always the silly season in Hollywood --

even for WAMPAS Baby Stars like Joan Marsh,

shown here adorned with necklaces, a bracelet,

and a ring hand-painted

onto her skin by Cecil.

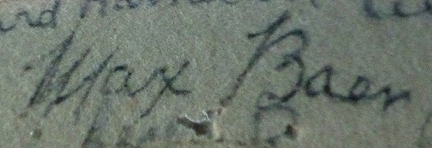

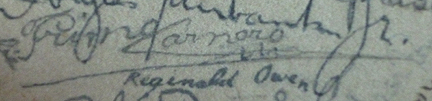

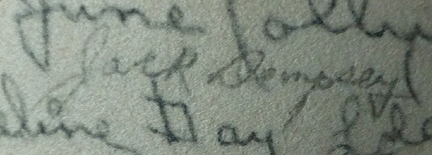

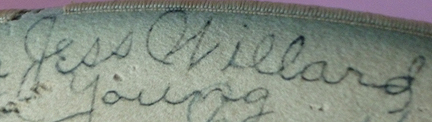

A

fascinating aspect

of the hat is how it conjures up the pop culture

zeitgeist of the

time. It wasn't just actors who signed the

hat.

M-G-M and other studios were constantly doing "stunt

casting" - taking

someone in the public eye and putting them in the

movies. A

great example is 1933's "The Prizefighter and the

Lady." For

their appearances in this film, four future, present

and past World

Heavyweight Boxing Champions - Max Baer, Primo

Carnera, Jack Dempsey

and Jess Willard - sat in Cecil's chair and signed the

hat for him.

Max Baer

Max Baer

Primo Carnera

Primo Carnera

Jack Dempsey

Jack Dempsey

Jess Willard

Jess Willard

Max Baer is the Prizefighter. Myrna Loy

is the Lady.

Max Baer, Jack Dempsey and Primo Carnera in

the ring in "The Prizefighter and the Lady."

The film, a romantic

drama, stars Myrna Loy opposite Max Baer as a boxer

who fights Primo

Carnera (playing himself) in a quest to be the next

World's Heavyweight

Champion. This clairvoyant casting mirrored

Baer's and

Carnera's professional status in the world of

boxing. Shortly

after this movie was made, Baer actually defeated

reigning champion

Primo Carnera for the Heavyweight title.

Myrna Loy once

remarked that Baer carefully studied Carnera's

boxing technique during

filming and used what he learned to best Carnera.

The

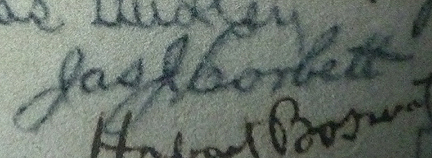

fifth boxing champ

to autograph Cecil's Stetson was James J. Corbett,

popularly known as

Gentleman Jim and known to be the "father of modern

boxing."

Corbett won his title in 1892, knocking out famed

boxer John L.

Sullivan. Errol Flynn starred as Corbett in

the 1942 Warner

Brothers biopic - "Gentleman Jim."

James Corbett

James Corbett

Gentleman Jim

Corbett in 1897.

Cecil

also got the autographs of those

famous folks of the time who must have just been

passing thru the M-G-M

Make-Up Department. "Red" Grange, the most

celebrated college

football player of perhaps all time, signed.

Red

Grange

Artist

Charles Dana Gibson,

the creator of "The Gibson Girl" and for whom

the Gibson Martini may

well have been named, signed too.

Charles

Dana Gibson

Charles

Dana Gibson

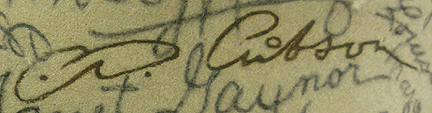

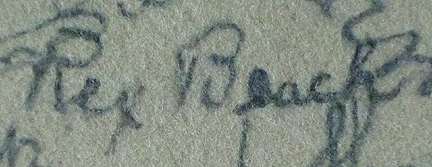

As did Rex Beach, an adventure novelist once as

famous as Clive Cussler

or Robert Ludlum.

Rex Beach

As

well as Roscoe Turner, a pilot and champion air

racer who wound up

on the cover of Time

in 1934. What an appropriately aerodynamic

signature.

Roscoe Turner

Did you

guess or do you give up?

They were

all nominated for a Best Actor or Best

Actress Oscar in the

first decade of the Academy Awards.

Granted, there

wasn't quite the hoopla and ballyhoo about

the Oscars back then as

there is now, but in their time, they were

all household names and

wildly famous.

Want

to

try

another list of hat signers? This one

will be

easier for some of you.

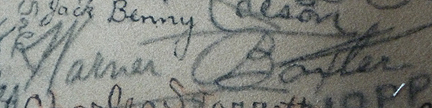

Warner

Baxter

Warner

Baxter

Alice

Brady

Alice

Brady

Victor

McLaglen

Victor

McLaglen

Ready for

the answer?

They

all

won

acting Oscars in the first 10 years of the

Academy

Awards.

(Although in the case of Brady, it wasn't an

Oscar statuette, it was a

plaque. This distinguished a

supporting award from a lead

award. Sheez. Hollywood.)

ALICE

BRADY'S OSCAR

A plaque, not a statuette.

The

prosaic point

being:

fame can evaporate faster than water

in the Mojave. In fact, it almost always

does.

Martin Scorsese's "Hugo" shone a klieg light on how

utterly forgotten

film pioneer Georges Melies was less than 20 years

after making

hundreds of ground-breaking films. And,

that's

normal, although there are rare exceptions.

The eternal fame

of a Gable or a Crawford can be traced to the fact

that people still

avidly watch their films because their

personas - against all

odds - still resonate with movie watchers. The

fame of a

Chaplin or a Pickford is more interesting.

People know of

them as historical characters, just like George

Washington or Abraham

Lincoln, not necessarily because they sit down and

enjoy the pictures

they made.

But for

most of those

who autographed "The Hollywood Hat," fame had an

expiration

date. When the movies went from silent to

talkies, lots of

big-time careers did crash. Sometimes, it was

because of their thick foreign or regional accents

and sometimes it was

because

their style of acting, perfectly appropriate for the

"silent" era,

seemed overwrought, florid, and, to be blunt, too

clunky for

talkies. Dialogue totally undercut their mojo.

It

doesn't

have to be something as catastrophic as a technical

revolution to send a career off the

tracks. There

comes a

time in most stars' careers when the public is tired

of them, when what

they have to offer no longer matches up to current

manias, tastes and

styles. When that happens, some, like Garbo or

Shearer,

retire and never look back. For all the

others, it must have

been quite painful when we, the public, muscled them

aside and just

moved on. Darwinism works in pop culture the

same way it

works elsewhere.

"The

Hollywood Hat" sprang to life in an era when all of

this drama was

first transpiring. I've lived in Los Angeles for

years now, and when I

drive around town, I see the studios, large and

small, that are still

standing and I see the 1920's Spanish-style mansions

on the windy roads

of the hills and canyons, and often think:

what was it like

back then, when all this was fresh and new and

happening for the first

time? Why can't Woody Allen do "Midnight in

Hollywood" and

send a chauffeured Duesenberg to take me back 85 or

95 years?

After

reading about all of the rollercoaster lives of the

hundreds of

people who signed the hat and how they, like Cecil

Holland,

serendipitously came to participate in the creation

of an entire

industry and art form, it certainly seems like it

was more exciting

back then.

And if I

could meet Cecil Holland, the first thing I'd say to

him is

"thanks for creating the hat, Cecil. It's been

quite an

education." And, then I'd let him do the rest

of the talking.

|